Rikk Agnew: Adolescent No More

Leaner and meaner, the godfather of the OC punk sound looks back on his life (and near-death) experience as a legend

By Nate Jackson ( https://www.ocweekly.com/rikk-agnew-adolescent-no-more-6430781/ )

The demon inside Rikk Agnew is the kind punks pay to see. Screeching feedback jolts through his body, provoking a maniacal grin. His black eyes bulge as he stabs at his guitar strings, his jaw clenched, a thousand-yard stare. The crowd can’t get enough.

On Dec. 30, 2010, an explosion inside his gut caused Agnew to retch and spit up blood on the steering wheel of his red Toyota pickup. . . . Up until a week earlier, his daily regimen consisted of a fifth of whiskey, an 18-pack of beer and vodka.

It’s Friday night at the Doll Hut, Anaheim’s reclaimed punk-rock roadhouse, barely six months since the landmark venue reopened after its wayward period as a banda-pumping paisa bar. The club isn’t the only thing looking restored tonight: Agnew, once slovenly and bloated, is onstage in a fitted, referee-style shirt to match his skintight black pants and thin locks of dyed, jet-black hair.

Three succinct stick clicks from the drummer signal the explosion of “Amoeba,” with its catchy, shout-along chorus made famous by his old band, the Adolescents. The pristine candy-colored nails on his bony fingers grip his guitar pick with white-knuckled intensity. Fists rise up, as shouts hit the rafters. “Amoebaaaaa! Amoebaaaaa! Amoebaaaaaa! Amoebaaaa-aaaa!”

The noise becomes so loud that Agnew hoists his guitar off his shoulders and lets it hit the floor. He jumps into the crowd and storms out the open double doors leading to the back patio. The band continue to play. Concern and confusion ripple through the Hut. From the side of the stage, a drunk fan playfully squawks, “Wooo! That’s classic Agnew right there!”

Yes, the 55-year-old legend has thrown his guitar and walked offstage more than once in his day. In the Punk Hall of Fame, Agnew’s level of onstage tantrums, excess and antics are infamous. And despite his newly polished outer shell, in that moment, it appeared the old Agnew was back.

But hiding in a shadowy corner of the outdoor patio, the godfather of the OC punk sound is feeling triumphant. The walk-off routine is just a gag, Agnew says. His manager, Daniel Darko, played along by trying to block people from entering the patio, insisting Agnew “needed a little space.” With his dark-haired fiancee, Gitane DeMone, sitting beside him, Agnew can’t help but laugh at the little scene he’d created.

“Yeah, it was all show,” he says. “I still love that part of it—I’m not gonna lie. There’s just something about creating a stir that appeals to me. I don’t really mean anything by it. Now, it’s all just fun.”

But for an old, out-of-control punker reformed by sobriety, good health, love and family, sometimes it’s good to know that at least part of the demon inside him still exists. The name Rikk Agnew has always been synonymous with Fullerton punk and Goth-rock royalty. A list of his old bands reads like a who’s-who of OC’s mosh-pit forefathers: the Detours, the Adolescents, Social Distortion, D.I. and plenty more, including an early-’80s stint with LA Goth rockers Christian Death. “I’ve been in every band except the Beatles and the Osmonds,” he jokes. The number of musicians influenced by Agnew’s layered, melodic guitar tones and soloing ability is infinite.

“People were calling him the Brian Wilson of punk,” says the Adolescents’ bassist, Steve Soto. “And he was.”

Unfortunately, Agnew and the famous Beach Boy shared some unhealthy similarities. Much of Agnew’s career was marred by alcoholism, drug abuse and depression on top of morbid obesity. There’s no way he’d be alive today had he continued down the path he was on.

That much, at least, became clear on the night before New Year’s Eve 2010, when a spontaneous explosion inside his gut caused Agnew to retch and spit up blood on the steering wheel of his red Toyota pickup. Agnew weighed 350 pounds, a massive white beard covered his double chin, his toes were like sausages, and the only shoes he could fit in were house slippers. Up until a week earlier, his daily booze regimen consisted of a fifth of whiskey, an 18-pack of beer and any vodka that happened to be within guzzling distance. That was on top of copious amounts of recreational pot, speed, meth, whatever.

He’d quit everything cold turkey, in part because he couldn’t get a buzz no matter how much he ingested of any particular drug, but now, in the driver’s seat of his truck, his body was telling him it was too little too late. “I had cirrhosis of the liver, an enlarged spleen, edema, anemia, you name it if it starts with an A,” he recalls. “I was a mess.”

According to his doctors, that was a distinct understatement. In fact, they calculated, Agnew had just three months to live.

Before being a heavy hitter in the punk scene, Richard Francis Agnew Jr. had always been sensitive about his weight. Half Irish and half Mexican-American and raised in a blue-collar, Fullerton neighborhood, Agnew says he was always teased over it. Shy and full of a childlike vulnerability that followed him into adulthood, the outcast quickly gravitated toward music for comfort. He remembers coming home from school and strumming heavy, pissed-off chords on a family guitar. Naturally, his younger brothers Frank and Alfie were his first band mates. They often jammed on a flotsam of instruments the family had scattered around the house.

“None of us was a good skateboarder,” Frank says. “So we stuck with the instruments.”

Over time, they all became capable, well-rounded players. In the spring of ’76, the first Ramones record hit, followed in ’77 by the dark, spastic freakouts of the Damned. And just like that, Agnew found an identity. Of course, most people in the suburbs thought punk was a nuisance. It wasn’t uncommon for guys such as Agnew and Social D’s Mike Ness to get their asses kicked by jocks or pelted with beer cans by truck-driving OC rednecks.

When Agnew’s friends in the local band the Detours invited him to join them in the summer of ’77, there were maybe a handful of punk or new-wave outfits in the county, and they all hung out together: the Detours, Social Distortion, the Adolescents, Berlin and the Mechanics. Crowded inside late Berlin drummer Dan Van Patten’s Fullerton condo, they often got smashed and pounded out Ramones covers on a grand piano.

As with Ness and some of his friends, Agnew fully embraced the punk look before there even was a look. One day, he’d show up on friend Steve Soto’s doorstep wearing a leather jacket and resembling a mascara-wearing murderer, and the next he’d be at a party dressed like a genie. “That’s how great punk rock used to be back then: There was no uniform; it was just weird,” says Soto, who got his start playing with fellow legends Agent Orange. “And Rikk was weird. He was just always a character.”

The Detours practiced in a makeshift warehouse called the Chicken Coop near Placentia off Orangethorpe and the 57 freeway. It was basically a dirty barn-looking shack with one powered extension cord in a Hispanic neighborhood with cockfights next door on the weekends. Soto’s next band, the Adolescents, which Agnew’s brother Frank co-founded as a guitarist, also kept their gear there in ’79.

Though Agnew proved to be an explosive drummer for the Detours, he was destined to be a songwriter and guitar player. Detours front man Gordon Cox still smiles as he listens to a recording of one of their early, screwball jam sessions during which they all decided to swap instruments. He points out the solo in which he says Agnew truly blew them all away with his raw, Hendrix-like aptitude for the sixth string. “When we heard that, the bass player and I both looked over at each other and went, ‘Oh, my God, we’re gonna need a new drummer now! Rikk’s gotta play lead!'”

Once he switched to guitar, Agnew wrote what would become an undeniable stable of classics, including “Creatures,” “Rip It Up,” “Kids of the Black Hole” and the music for “Amoeba.” But when the Detours stalled out for a time in late 1980, Rikk and Casey Royer joined Frank in the Adolescents along with founders Soto (bassist) and Tony Cadena (vocalist). The four of them, the band’s classic lineup, wrote and recorded their 1981 self-titled debut known as The Blue Album. “Rikk’s songwriting was really adventurous for punk rock,” Frank says. “He was writing stuff that was punk but had a Beatles-esque quality with the guitar harmonies.”

Agnew’s best work by far was “Kids of the Black Hole,” named after Mike Ness’ legendary Fullerton apartment, a graffiti-covered drug den fed by a steady diet of parties, sex and violence. To date, there hasn’t been another song quite like it. “To me, it is one of the greatest punk-rock songs of all time,” Soto says. “And of course ‘Amoeba’ was catchy as fuck, and everybody wants to hear it. But to me, ‘Kids of the Black Hole’ was like ‘Quadrophenia’ for us.”

Though Agnew had contributed heavily to the band’s most influential album, months after its release in 1981, the fun was wearing thin. Ego-fueled skirmishes between him and other members were boiling over constantly. During one show at the Starwood in LA, Agnew abruptly threw his guitar and walked offstage. He wouldn’t take the stage with the band again until they regrouped in 1986; two years later, after the recording of 1988’s Balboa Fun*Zone, he left again. His onstage antics continued; once Agnew smashed his amp on the ground outside a show in Boston because he said the devil had possessed it.

Usually, Agnew’s drug-fueled dramas involved destroying something; in some cases, they included making things permanent. “In the middle of our recording the song ‘Tattoo Time,’ you hear a tattoo gun going on,” Agnew says. “That sound is actually me getting tattooed, and we recorded it.”

Today, Agnew’s heavily inked limbs are practically a time line for every band he has been in. The faded ones are true band tattoos. He has a scroll carrying the old Detours motto on his arm (“Be Proud, Live Fast, Carry On”), the D.I. logo near the inside of his elbow, various Goth imagery all over him, some commemorating his Christian Death days. He also has a seemingly random logo for Public Enemy tatted on his chest (not because he was in the band, obviously, just a huge fan).

The years between his stints with the Adolescents wound up being some of the most creatively fertile years of Agnew’s early career. He rejoined the Detours briefly, until they called it quits in ’82, and then he indulged his dark side, linking up with late singer Rozz Williams in Christian Death. Agnew co-wrote most of the songs on the seminal Goth debut Only Theatre of Pain, but he bowed out of the band shortly after the record was released.

Sometime around 1983, Agnew was trying to figure out what to do with his decent catalog of unrecorded material when he ran into friend and 45 Grave keyboardist Alex Gibson, who suggested he was talented enough to go solo. “I didn’t know what to do, and [Gibson] was like, ‘Rikk, you already play all these instruments. Why don’t you just do a whole album by yourself?'”

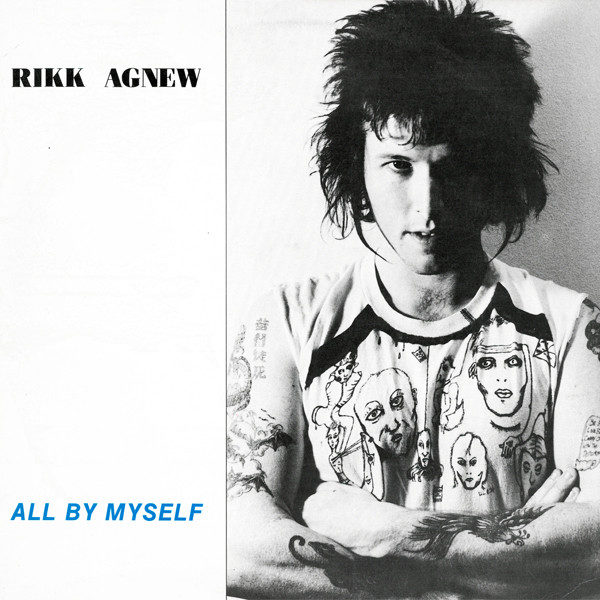

With financial backing from Lisa Fancher at Frontier Records (the label that put out The Blue Album), the then-23-year-old Agnew drove to Sun Valley’s Prospective Sound from Fullerton after work for three straight days to piece together a solo record with former Adolescents producer Thom Wilson for a whopping $1,500 budget. In just two or three takes apiece, he recorded the guitars, bass, drums, keys and random sonic flourishes. The end result, aptly titled All By Myself, produced a number of great songs, including the angst-ridden anthems “Falling Out,” “Section 8” and “OC Life”—all of which he still plays at shows.

The lyrics paint a timeless picture of an outcast’s frustration in the ‘burbs: “Wanna be a member, wanna be a name/Wanna be a local hero, play the social game/Locked into a time warp with your dinosaur trends/The limits of your mind is where the county line ends.”

At the time, Agnew says, he caught a lot of flak for recording as a one-man band and having the gall to add a poppy love song called “Everyday” to the track list. Some even called him a wannabe Paul McCartney and a sell-out. “If I was selling out, I’d have been writing ‘Amoeba’ every time,” Agnew protests. “Just because it sounds more accessible or more pop—that’s called an artist fulfilling his own needs and progressing and branching out.”

Despite the hate, Agnew continued to perfect his orchestration of layered guitar melodies over swift punk beats in bands including D.I., with former band mate Royer, who was hopelessly addicted to heroin. Agnew wasn’t quite as far gone as Royer (who was arrested for overdosing in front of his son in 2011), but he still drank, snorted, injected and smoked his way through the ’90s and early 2000s. In 2001, Agnew joined up for another Adolescents reunion, but he showed scant enthusiasm, overloading his schedule with other projects, drinking excessively and doling out more guitar-chucking, half-assed performances. His increased weight gain was almost a barometer for how much he didn’t care.

“None of it made me happy anymore,” Agnew says. “I loathed it. But I had to step back and go, ‘Wait, [music] is what saved me. This is what I love; this is my best friend, my lover I’ve been with forever. It was there for me even when nothing else was or no one else was.'”

Despite pleading from family and friends, Agnew continued to use drugs, often disappearing for days at a time. Finally, in 2006, Detours band mate Gordon Cox and friend Steve Gee tracked him down in an apartment in Costa Mesa. Agnew was camped out there, getting high on meth, and Cox and Gee found him in a daze. “I’m ready to go now,” he told them. The two friends immediately drove Agnew to rehab at the Blue House in Newport Beach. The move, though well-intended, was a short-term fix. True sobriety would take three more years of self-abuse and a three-months-to-live prognosis.

Today, it’s almost impossible to recognize Agnew from the person he was back then. He has lost about 140 pounds, practices yoga or works out each day, and is one or two carrots shy of being a vegetarian. You can see it in his face and lack of sweat as he helps DeMone hustle in some equipment. The couple are setting up for a late-night show on the concrete floor of a small art gallery off the Twentynine Palms Highway in Joshua Tree. At one point during the set, DeMone turns her back to the crowd while she harnesses her black rubber strap-on. Strutting and thrusting her hips, Agnew looks on with amusement before diving into a dexterous solo as DeMone’s ominous, jazz-inspired vocals fill the room.

Agnew and DeMone, who became engaged in 2013, both have daughters (Polli and Zara, respectively) from previous relationships and have known each other for years. They were both members of Christian Death, albeit at different times. Though she’d only heard about Agnew through friends. DeMone used to pack and ship band T-shirts to him for his various projects while working at Radiation Records. A Goth queen in her own right, DeMone’s talent as a roaring vocalist earned Agnew’s respect. “She’s one of the few people who I can describe things to musically, and she understands and vice versa. We don’t speak the regular language. . . . We have our own language, I guess.”

Since meeting, DeMone has made a successful effort to keep her new beau healthy and exercising, a feat that only paid off after Agnew decided to give up hard drugs and booze and start focusing on his life. “When I finally knew I was going to die, I lost all the desire for the stuff I was doing,” Agnew says. “I don’t miss it at all.”

Though Agnew has changed a lot physically, his musical tastes haven’t. He’s still driven by his dual passions for punk and Goth. Obviously, the Goth part is satisfied by performing with his lady. And the Rikk Agnew Band, which he started earlier this year with the members of local band Wrong Beach, is his other main project. Agnew has once again polished his solos and layered guitar chops to play a host of new songs, classics from the Adolescents and his solo albums, and the song he sat on for seven years, “I Can’t Change the World.”

Sam Hare, the band’s guitarist, has been so influenced by Agnew that he wanted to start making a documentary on him in 2005. After a number of meetings and filming sessions over the past decade, when it came time for Agnew to put a band together, Hare (who fittingly rocks a bone-straight, back-length heavy-metal mane) was asked to join. “I always felt that Rikk would be an excellent subject for a documentary,” Hare says. “And as a fan who now gets to play with him, this is the ultimate dream. . . . I owe him everything.”

At this point in his life, Agnew insists there’s little reason to be scared about being in a band with him, even with his occasionally fake walk-offs. He has even found a constructive way of dealing with the inevitable band fights that will arise when the group goes on tour this summer. It still involves fighting, just with boxing gloves and face masks. He figures it’s a more honest way to deal with conflicts, instead of letting them fester like he used to. Even though he’s the oldest one in the band, he’s learned there’s a balance between believing in himself, showing maturity and staying young at heart.

“I gotta do this right and learn to be confident. Now, I’m more confident than I’ve ever been in my entire life,” Agnew says. “And a lot of it has to do with the people around me. You are the company you keep.”

On a recent summer day, Agnew is at a barbecue at his brother Alfie’s house, surrounded by friends and family. The smell of grilled burgers wafts over the backyard pool, not more than 2 miles from the Agnew family’s original home in Fullerton. Alfie grew up to be a physics professor at Cal State Fullerton and plays in a punk band called Crash Kills 4. Younger brother Frank also gets onstage with 45 Grave when he’s not working his day job in the computer industry. His parents, both still alive, are proud of all their sons, including the eldest, who, some might say, took the longest to get it together.

But in the company of punk pals from back in the day, swapping stories about ass beatings and hazings both given and received, everybody here is entitled to feel young again. That includes Agnew’s right to make a ham out of himself on the edge of the diving board, as he jumps into the crystal-blue deep end with all his clothes on. These days, he’s happy to cause a moderate splash instead of a tidal wave. Calmly floating face down beneath the surface of the pool, Agnew is finally in a pretty good place, his health and sanity intact.

The man who has made such an impact on Orange County music is content knowing that whatever fame people want to ascribe to him is nice, but not essential. Making a living that lets him keep playing is all he’s ever wanted. His music doesn’t need to change the world, but it’s changed his. And for him, that’s enough.

“People ask me, ‘Don’t you think you could’ve done so much more in your career if you weren’t such a fuck-up for so long?'” Agnew says. “All I can really say is, ‘All roads lead to now.'”